India made efficient LED lightbulbs ubiquitous and cheap in just three years. It has an opportunity to do the same for super-efficient appliances and create a massive new global and domestic market, says innovator Sundar Muruganandhan.

India’s state-run Energy Efficient Services Ltd.’s (EESL) Ujala program proved that the purchasing power of government can scale new products. By enabling bulk procurement of LED bulbs, EESL drove the cost of LEDs down by 90% from 2014 to 2017, while creating a new domestic manufacturing sector (India aims to bring LED bulb imports to zero by 2020) and opening up a huge consumer market of more than 270 million LEDs (so far). In addition, the conversion to LED bulbs resulted in energy savings of over 3275 kWh of power and helped avoid peak power demand equivalent to six thermal power plants each with 1000 MW capacity. According to some estimates, this has helped save ₹400 billion rupee (USD $6.1 billion).

So why stop at lightbulbs?

The Indian government has the opportunity to create similar scale for super-efficient appliances, and by pairing them with distributed solar, deliver energy services at affordable prices to its 300 million unelectrified population.

An obvious starting place: ceiling fans. 40 million fans are bought each year in India, making it the world’s largest consumer market. In a tropical country like India, fans are probably the most important appliance. Yet, current fans on the market are highly inefficient, operating for minimum 14 hours a day in southern India while consuming more electricity than refrigerators that operate for 24 hours.

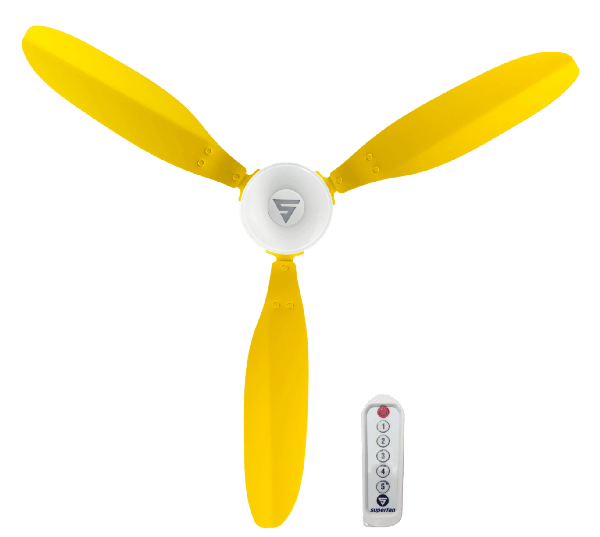

True, fans are more complicated than LED lightbulbs, with more components and materials. But according to Muruganandhan, the founder of Superfan, an award-winning Indian company pioneering new efficient fan design and manufacturing, the barriers are not difficult to overcome.

“Someone needs to aggregate demand and buy in bulk,” Muruganandhan told Power for All. “We can actually achieve the necessary cost reductions, but we need a guaranteed offtake.”

Right now, even though Superfan products are more durable and deliver a 56% reduction in electricity consumption vs. standard fans while maintaining the same air flow and offering a 5-year warranty (warranty is critical to reassure the rural poor for whom appliances are a major investment), they cost twice as much as normal fans. Scale, and some additional innovations, are needed to do change that.

EESL attempted to create scale for ceiling fans in 2016. It issued a tender for 1 million efficient fans (Superfan was given a quota of 162,000 at ₹1360 rupees, or USD $21, per fan). The goal was to sell fans at ₹1,680 rupee, nearly half the previous market cost. But since then — nothing. The program was never initiated. But just this week, EESL received $454 million in funding for energy efficiency projects from the GEF (Global Environment Facility), including five-star rated ceiling fans.

Superfan already has licensed new blade technology to increase efficiency even further and is ready to scale (it has sold 100,000 units over the past 5 years). With some other minor tweaks by the government — including lowering the Goods and Services Tax (GST), which is now 28% — “we could do great things”, he added.

A demonstration of what’s possible by combining super-efficient appliances with distributed renewables to deliver energy services to India’s last-mile communities is currently being run by Smart Power India, an initiative that is working to scale mini-grids. Customer acquisition costs are high in rural India, so increasing village-level power consumption beyond just lighting is a key to making mini-grids more commercially viable. And key to that is delivering power along with super-efficient, affordable appliances.

“We’ve seen great adoption,” said SPI’s special initiatives manager Umang Maheshwari. “Specifically, people were very happy with the Superfan, which was the highest selling product.” Interestingly, SPI found the fan appealed more for its remote control and design aesthetic, not just its efficiency.

SPI ran an initial six-month pilot at about 30 mini-grid sites in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand states to test consumer interest in fans and TVs, and is now focused on achieving 30% customer penetration of the two appliances at 8 sites for a second pilot ending in December. The 30% mark is the minimum threshold to allow SPI to truly understand the impact on mini-grid plant economics.

Maheshwari says that the potential for TVs is even larger than fans, because they are not seasonal and offer family entertainment. But more sophisticated supply chain and financing is needed. While consumers can afford to buy fans up front, TVs are a bigger ticket item and need financing. Mini-grid developers have found it difficult, however, to attract the attention of micro-finance institutions because they haven’t achieved necessary scale yet.

But the pieces are largely in place to replicate India’s success at scale with LEDs. EESL just needs to flip the switch.