Productive use is one of the hottest buzzwords in the world of energy access today, increasingly used by development banks, industry leaders, and civil society organizations (among others!) as the work to deliver energy to 1 billion people evolves beyond just lighting.

But what does “productive use” of energy actually mean?

It seems intuitive, but there is no clear sectoral alignment on what is or isn’t productive. The answer is important, because without a more unified understanding, our efforts could potentially be counter-productive.

Traditional definitions of ‘productive use’ presume that it does not include technologies primarily suited for household, community (health and education), or consumptive use, but rather technologies utilized in agricultural, commercial, and industrial activities that result in the direct production of goods or provision of services.

In fact, a recent analysis explicitly challenged the potential of basic and household appliances to improve livelihoods and enable continued growth in the off-grid sector: “For PAYGO to thrive, incomes need to rise. While many will argue that using energy devices such as lights, fans, fridges, and TVs enhance productivity, there is limited evidence to suggest that they have significant impact on household income beyond delivering savings relative to alternatives.”

As alluded to in that assertion, it seems that increasingly the unifying principle for defining something as productive is that it generates new income. Another recent analysis cut straight to the point and proposed that productive use be replaced with “Income Generating Appliances” to help clarify things.

But if income generation is the main objective, new data emerging from the sector suggests a lot of other technologies should qualify.

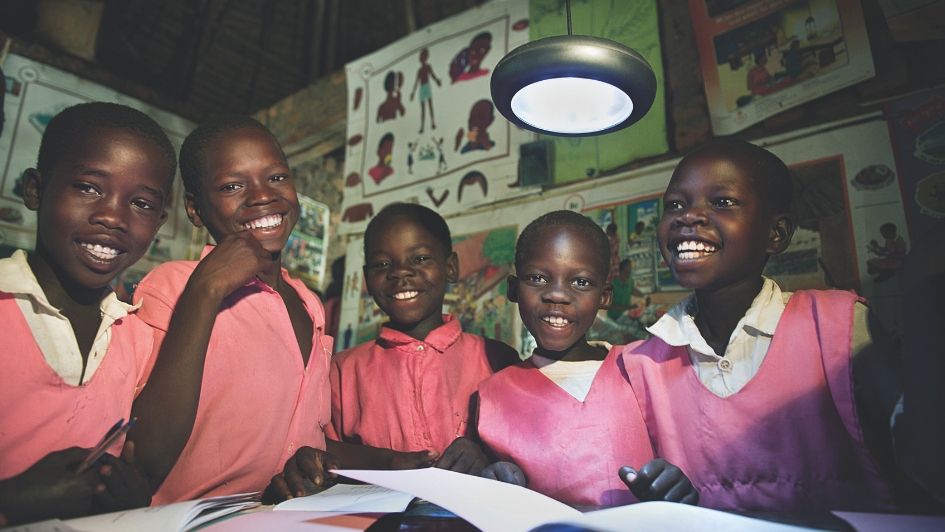

Lighting, for example, can be a transformative income generating technology. This is no longer speculative, as GOGLA’s recent Powering Opportunity report asserts that “access to electricity has already enabled [an] increase [in] monthly income by $35 a month” for one-third of solar home system customers.

Access to electricity in this instance meant lighting, and a light bulb that allows a shop to stay open later or a small business of any kind to extend its working hours is rightly characterized as a direct driver of income.

Household appliances can also be transformative from an income generation perspective. Preliminary impacts assessment data from the Global LEAP Off-Grid Appliance Procurement Incentives Program shows that high quality off-grid TVs and fans helped micro-enterprises attract more customers and increase revenue. For example, an entrepreneur in Kenya opened up a village movie hall with a home solar package from Mobisol that included a 32” flat screen TV financed through the Global LEAP program. The only video hall on a remote island, his modest facility is now the gathering point for dozens of villagers to watch the news, movies, and football games and he now makes on average $6/day from charging entry fees for viewings. With the extra money he’s saving, he plans on buying his own piece of land and building a house for his family.

Similarly, in Bangladesh, the owner of a small retail shop with a highly unreliable grid connection (frequent power outages of up to 10 hours per day) decided to invest in a solar home system with a TV and fan sold by Rahimafrooz Renewable Energy Ltd. to attract more customers to his shop during the 2018 FIFA World Cup. He subsequently reported a 25% increase in his business just 3 months after purchasing these appliances.

Clearly, new insights on the livelihoods impact of small-scale solar technologies are challenging conventional wisdom.

Individual donors and investors are rightly launching new initiatives to scale markets for large, energy-intensive, and costly productive use technologies. Donors and impact investors interested in these technologies must have higher risk thresholds than conventional financiers. More sources of (very) patient capital are needed for some of the most compelling and commonly-cited productive use technologies like off-grid cold chain solutions and solar-powered agricultural mills.

Most early movers in this part of the sector—such as the ten innovative companies shortlisted in the Global LEAP Off-Grid Cold Chain Challenge—are still struggling to demonstrate the viability of their technology in high-risk, low-margin markets and value chains whose fundamentals are even more challenging than the household solar market. Support for the development of a technical foundation for these product markets—including standardized approaches to product testing and quality assurance, something the Efficiency for Access Coalition is working on—and a more realistic understanding of the current state of play will help companies on the ground to eventually prove the potential of these technologies.

These efforts could be complimented—and potentially strengthened—by a market ecosystem that more clearly acknowledges the broader livelihoods impacts of smaller solar products and household appliances. Such acknowledgement could unlock additional resources to support the rapid scaling of these markets.

The temptation to pick winners and losers in terms of which products and equipment may be most impactful or productive is strong, but in such nascent markets could result in siloed, uncoordinated—or worse, unbalanced—investment. More research on the broad range of economic impacts unlocked by distributed renewables in off-grid communities and greater recognition of the clear potential for these products to improve livelihoods could help mitigate this risk.