The government has launched an innovation challenge that hopes to revolutionize access to electric induction cookstoves by taking advantage of huge cost declines in solar PV. Cheaper batteries are the “x factor”. Health and climate benefits are the prize.

SDG7 — affordable, modern, reliable, sustainable energy for all — includes providing access to electricity (for 1 billion people) and clean cooking (for 3 billion). But the two have always been on parallel tracks. Clean cooking has focused on cleaner biomass-fuel or LPG stoves. Electricity has so far focused mostly on solar lighting. But the tracks may be set to merge into one, with the encouragement of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

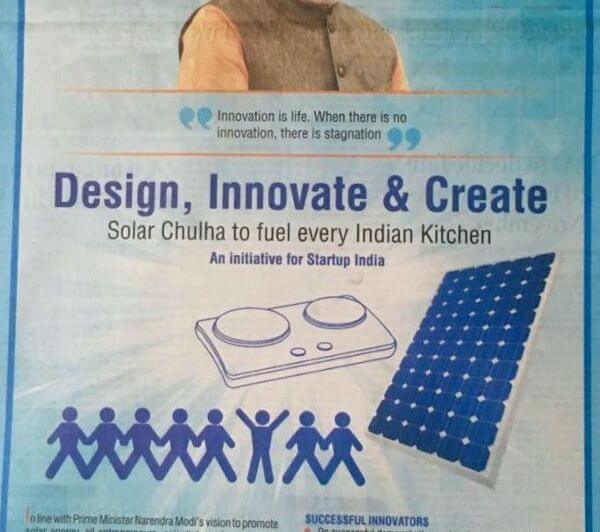

Oil and Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC) and Startup India have launched an innovation challenge to create a “Solar Chulha to fuel every Indian Kitchen” (a chulha is the Hindi word for stove) and meets the following criteria: safe for indoor use; boils, steams and fries; grid and off-grid compatible; serves a family of five; available for use 24 hours per day; battery storage that cycles 2,500 times; sustainable and easily available materials, and a cost of under 10,000 rupee ($155) per unit. Registration is online with a December 1 deadline. Applications are due April April 15, 2018, and finalists will be invited to present at the end of April 2018.

“While the world is working towards electric cars, in India, in addition to electric cars, electric stoves would go a long way in meeting the needs of the people,” Modi was quoted saying recently. “This innovation would, in one stroke, significantly impact the nation’s dependence on imported fuel.”

Urban consumers in India already have a mature market for electric induction stoves. Induction stoves, which have heating performance comparable to gas burners but are significantly more energy-efficient and give off no harmful emissions, have become relatively inexpensive in recent years. That coupled with a steep decline in solar PV prices makes the chulha challenge quite compelling as a cooking solution for rural, remote households, which are also seeing rapid uptake of rooftop solar and green mini-grids. TERI researcher Debajit Palit has also noted that the distributed solar business model that has exploded in the past 5 years has much to teach the clean cooking sector, which has so far been unsuccessful in scaling or addressing indoor air pollution concerns. SEforALL CEO Rachel Kyte said recently that clean cookstoves remain “one of the biggest challenges in delivering the SDG on energy, and it is one of the objectives where the indicators show that the problem is becoming bigger rather than smaller.” She called for “a wholesale reappraisal” of the sector, stressing that investment needs to increase from tens of millions of dollars per year to billions.

But innovation in technology and systems integration is also required, as noted by the challenge organizers.

“The main barrier at present is the cost and lifetime of available batteries to provide the approximate 3 kWh of storage required to cook both evening and morning meals in a typical household,” according to ONGC Limited.

Anjali Garg, program manager at IFC’s Lighting Asia/India, said of the challenge: “It will be exciting to see the innovation and design ideas that surface. As we’ve seen in the solar lighting and super-efficient appliance sector, one of the key elements that needs to be considered in any new product design is a focus on quality assurance.”

About 700 million people in India live in households that cook every day with simple chulhas using locally gathered biomass for fuel. This results in substantial exposure to air pollution inside the home and is also an important contributor to outdoor air pollution — estimated to be responsible for more than 25% of the country’s outdoor air pollution. It also contributes to the premature death of more than 800,000 Indians each year, with the greatest risk for women and young children.

In addition, gathering biomass fuel often takes time that could be put to more productive uses and in some parts of India contributes to land degradation and deforestation.

The climate impact of reducing cookstove emissions is also significant. Residential solid fuel burning accounts for up to 25% of global black carbon emissions, about 84% of which is from households in developing countries Black carbon is a byproduct of poor or incomplete combustion and is estimated to contribute the equivalent of 25–50% of carbon dioxide warming globally.